Dr. Prabhakar Tamboli was born in 1928 in Gwalior, India 190 miles south of New Deli. He was born to a middle class family. They lived in a temporary house where he walked nearly three miles to primary school. Prior to antibiotics and vaccines, he missed an entire year of his early education while he suffered from various illnesses.

Driven for a better life, he attended Victoria College while working for an auto body shop. He would wake up at 2:30 am to study before going to class. He clocked into the auto body shop after school for the day.

“After I got a job, so did my father,” said Tamboli. “My life improved considerably. Then my dad retired but had no pension.”

Tamboli persevered. He received his bachelor’s degree in chemistry and biology from Victoria College in Gwailor. He did his graduate work in soil science as a government fellow with the Indian Agricultural Research Institute in New Delhi. After graduating he stayed, becoming a lecturer.

As a chief chemist with government of Madhya Bharat, he established the first soils department for the state. Tamboli longed to get his PhD but funding was an issue. By this time he was married with two children and supporting his parents. He couldn’t make it work on a lecturer’s salary.

The trajectory of Tamboli’s life changed when he was selected as a Rockefeller Foundation Fellow. Over 300 applications and he was one of three awardees that year.

“I found myself in Ames, Iowa to do my PhD work in soils research,” said Tamboli.

His dissertation focused on the impact of tillage on physical properties of soil. Work that laid the foundation for what’s commonly known as no-till today.

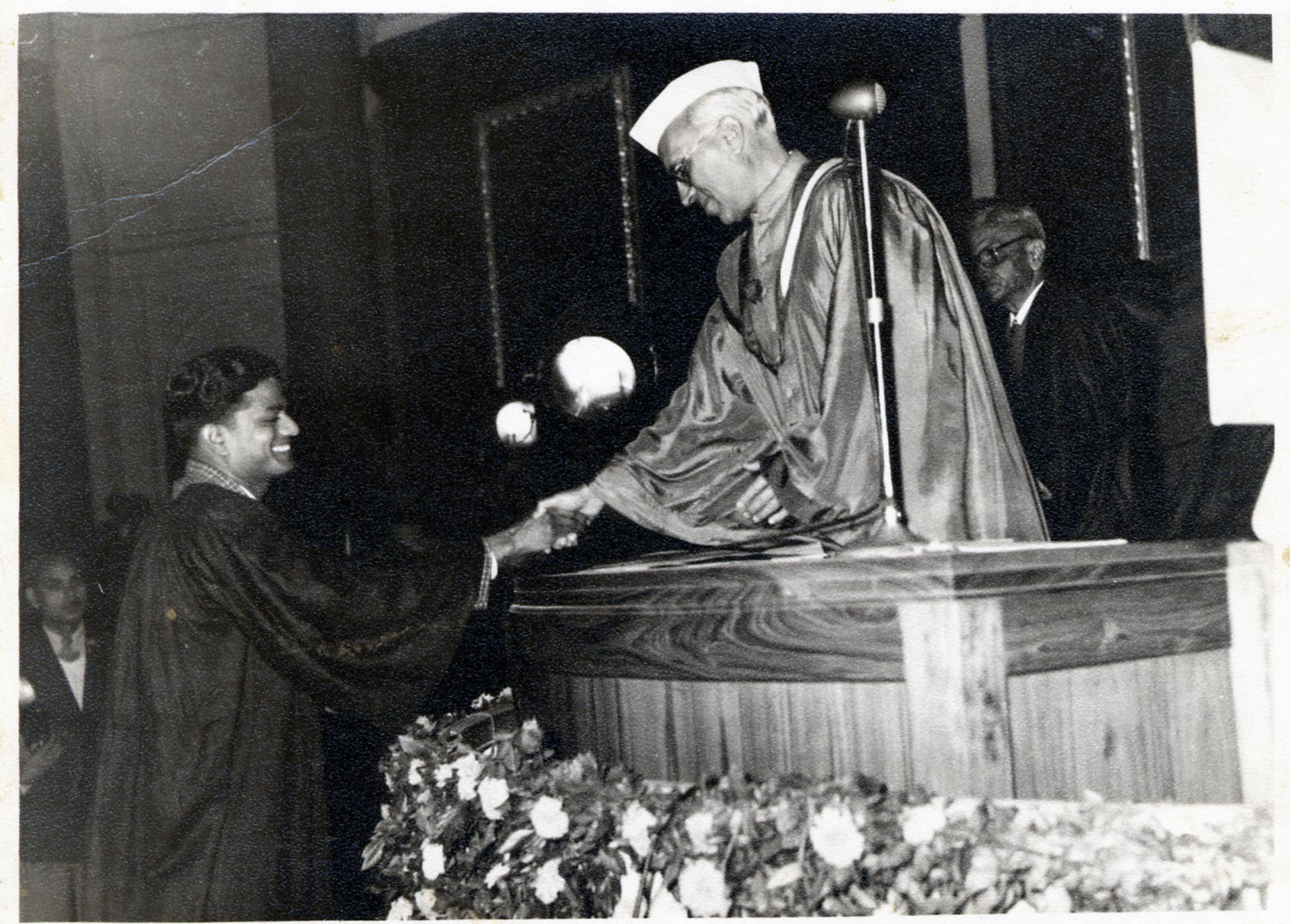

After earning his doctorate, Tamboli returned to India where became professor and associate dean at Jawaharlal Nehru Agricultural University at Jabalpur. There he established the soils research program in collaboration with the University of Illinois.

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) stepped up and funded Dr. Tamboli to establish soil testing facilities across the country.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) took note of the great work Tamboli was doing. He was a soil fertility expert for the organization based in Rome. He established fertilizer use for eight different crops in Afghanistan during his years with the FAO.

Then Tamboli was hired by The World Bank in Washington, D.C. As senior agriculturist, he worked on 17 countries in East Africa. He established training programs and crop production programs. Ultimately, he was transferred to Southeast Asia, where he provided guidance on the soils and agriculture sector for 18 years.

Upon retiring at 62, Tamboli decided now was the time to teach. Even today, at 93-years-old, Tamboli teaches an undergraduate course on international crop production challenges of 21st century at the University of Maryland. It has become an essential part of undergraduate agricultural education.

“I hope to educate and inspire these students,” said Tamboli.

It didn’t just stop at teaching. Tamboli leveraged his experience building training programs to invite people from developing countries to learn about modern technology that would be useful in their home countries. The governor of Maryland presenting him an award for international collaboration.

“Looking back, Ames was the most unique experience of my life,” said Tamboli. “I’d never seen snow in my life until I came to Iowa, and we got six feet that year. I couldn’t open the door of my apartment in Pammel Court. Never felt so much cold in my life.”

His Ph.D adviser, Dr. W.E. Larson . He quickly learned the most important things take time. He worked in the field with Drs. Larson and Kirkham. Dr. Heady, from the Economics Department and namesake of Heady Hall, was on his committee.

“I got such a rounded experience and training in different fields related to agriculture that increased my horizon of thinking of the entire system rather than the individual component,” said Dr. Tamboli. “Each part of the system has to be synchronized like the parts of a car. You can’t say one part is more important than the other. They’re all required to be successful.”

After a successful career in science, Dr. Tamboli asks his students to think big.

“What is your long-term and short-term goal in life,” said Tamboli. “Who is your mentor? In order to be successful in your career you need to follow your passion. Follow what gives you satisfaction and use that to set your course.”