When Michael Castellano tells people there are billions of different variations of farmer decisions and environmental conditions that can affect how much nitrogen fertilizer is just enough for a plot of corn, he’s occasionally chided for embellishing. Really? Billions?

“They’ll say, ‘Mike we get that it’s complex. You don’t need to exaggerate.’ But I’m not exaggerating. When you do the math, it’s literally billions of possible combinations of hybrid varieties, management practices, weather and other variables,” said Castellano, the William T. Frankenberger Professor of Soil Science and an Iowa State University professor of agronomy.

That uncertainty has big economic and environmental implications. Applying too little nitrogen hurts yields. Applying too much hurts profits because nitrogen is typically the most expensive input for corn production. Excess nitrogen in fields also contributes to water and air pollution.

Despite incentives to use just the right amount of nitrogen fertilizer on corn fields, current official recommendations are broad and ideal rates can vary widely from field to field and year to year. A research team led by Castellano and his ISU colleague Sotirios Archontoulis, Pioneer Hi-Bred Agronomy Professor, is collecting data from trials across Iowa – mostly in fields of participating volunteer farmers – to build models that offer far more granular guidance.

“This project is an investment that will help keep Iowa the best place in the world to grow corn and soybeans,” Castellano said.

The Iowa Nitrogen Initiative is supported with annual funding from the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship. Iowa Secretary of Agriculture Mike Naig said the nitrogen initiative is a strong collaboration between Iowa farmers and ISU experts.

“Farmers depend on the best science when making decisions about crop production, including nutrient management, crop inputs and conservation practices,” Naig said. “This important work will lead to data and tools that farmers will utilize to optimize nutrient management, boost profitability and protect our natural resources.”

Closing the gap

The Iowa Nitrogen Initiative is running 270 on-farm trials this year across 72 different private farming operations. That’s a 400% increase in trials from the project’s first year in 2022. The ultimate goal is 500 trials per year.

To participate, farmers need access to two increasingly common precision ag technologies: variable rate fertilizer application and GPS-based yield monitoring. Using historical yield data to choose spots expected to behave differently, project partner Premier Crop Systems designs a trial in a small area of a field, usually about five acres. Sections within the trial area are assigned varying nitrogen rates, from none up to 200 pounds per acre, and farmers provide the yield data to the research team after harvest. Participants are compensated for the loss of yield on land that receives no nitrogen.

Trial data is enriched with simulations from biophysical process models to calculate optimal rates based on soil and seed types, management practices and weather. That database will be the engine behind the project’s public-facing decision-making tools, which are expected to be ready to use for the 2025 growing season.

The tools will be especially valuable for farmers using the precision ag technology needed to collect the data. Farmers who have the equipment for applying fertilizer at a variable rate often have insufficient evidence-based direction on how those rates should vary, Castellano said.

“We’re trying to close the gap between the precision ag advances made by engineers and the scientific understanding of agronomists,” he said.

Three tools in the works

The research team plans to develop three decision-making tools:

- Updated and more dynamic benchmark recommendations for nitrogen rates will account for differences in genetics, soil, management and weather. Farmers also will be able to see anonymized data from trials to see the real-world outcomes of various rates and practices.

- Forecasting will estimate ideal rates based on current and near-term predictions for soil and weather conditions. That’s important because weather has a disproportionate impact on nitrogen rates, Castellano said.

- Hindcasting will help farmers look back at a prior growing year to explore how their crop’s nitrogen needs would have changed if they’d done things differently, from planting a different hybrid to applying at a different time.

Castellano said the goal is to continually refresh the tools with new trial data every year.

“As long as farmers are innovating and the weather is changing, optimal nitrogen rates will be changing. We need ongoing research to provide farmers the information to make the best decisions possible,” he said.

Farmers in the fold

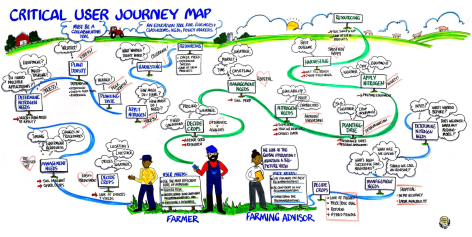

Farmers have been involved in the Iowa Nitrogen Initiative from the beginning, including a design sprint in February facilitated by Google engineers and designers. Feedback from farmers, for instance, is why the initial rollout of the decision-making tools will be a mobile app. They told project designers they’re more likely to use the information if they can access it on the go.

“We’ve been working hand in hand with farmers who have helped us make sure the products we’re developing are useful for the people who will use them,” Castellano said. “We don’t want farmers to feel this is forced on them.”

Castellano said he’s encouraged that every farmer who participated in the first year of the project continued in the second year. Roger Zylstra is one of those volunteers who has hosted two years of trials. At a field day in September at a university farm near Boone, he told the crowd that collaborating with the research team was as simple and seamless as could be, though he’s hoping for some wet years soon to provide more variations in the data.

“I always try to figure out how to be a better steward of the land, and we learn there are better way to do things,” said Zylstra, a former president of the Iowa Corn Growers Association who farms near Lynnville in Jasper County. “I think the potential here is amazing.”

Project leaders are recruiting farmers, crop advisers and custom fertilizer applicators to sign up for a trial in the 2024 growing season. Fill out an online form to express interest or seek more information.

In photo at top: Research aimed at providing Iowa farmers with far more precise recommendations for nitrogen fertilizer application rates relies on trials in fields across the state. At this Fayette County farm, the lighter-colored portions of the field are where little or no nitrogen was applied. Photo courtesy of Iowa Nitrogen Initiative.